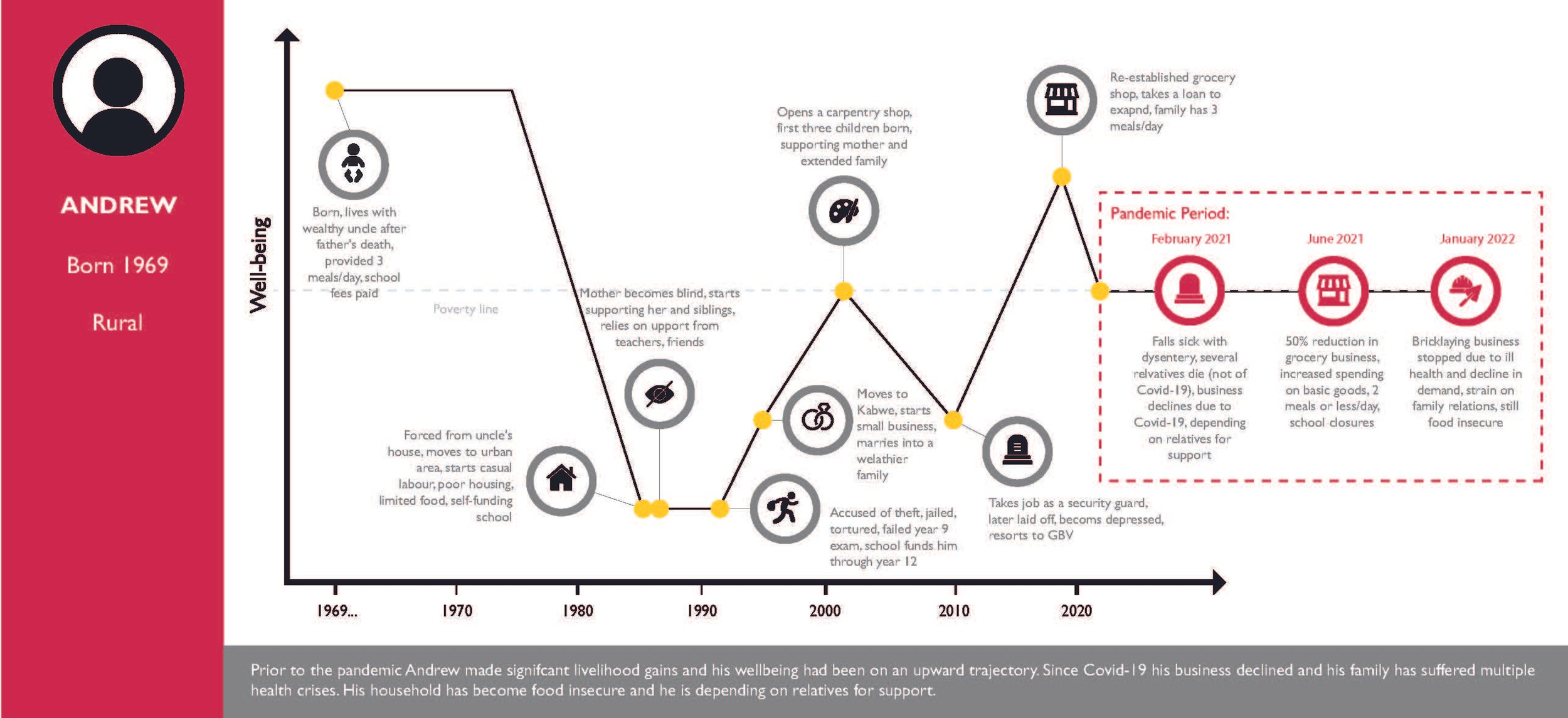

Impacts of the Government of Zambia’s Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic on Poverty

COVID-19 tested the social welfare system that successive governments have been building in Zambia over the last two decades. Zambia had one of the highest poverty rates in the world going into the COVID-19 pandemic as well as overlapping vulnerabilities related to climate change, macroeconomic instability, and high external debt. These and other challenges exposed many people living above the poverty line to impoverishment and pushed households living in poverty further towards destitution.

Civil Society for Poverty Reduction (CSPR), the Chronic Poverty Advisory Network (CPAN), and the Institute of Social and Economic Research (INESOR) have been monitoring the impacts of the pandemic on people living in or near poverty in Zambia since early 2021 in three districts – Lusaka, Kabwe and Chipata - about the reach and impact of these policies. This policy brief reviews the Government of Zambia’s key policies to mitigate the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on people living in or near poverty and summarises insights from people affected by these policies about what they have achieved and how they can be improved.

Poverty, Hunger and Jobs: Pandemic Update and Recovery Prospects

The COVID-19 pandemic and intersecting crises— including climate change, conflict, debt, and the ‘triple F’ crisis (food, fuel, finance)— have reversed progress on a range of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), increasing the number of people in poverty, contributing to a dramatic rise in hunger and food insecurity, increasing gender inequalities, and constraining the effectiveness of interventions to promote pro-poor livelihoods and decent jobs.

In many countries, the post-COVID-19 recovery has been slow and incomplete. To promote the joining up of SDGs (1- no poverty, 2- zero hunger, 8- decent work and economic growth), CPAN/IDS, IFPRI, Southern Voice, and the Global Donor Platform for Rural Development co-convened a three-day virtual international workshop in June 2023 on “poverty, hunger and jobs”. Its aim was to synthesise latest knowledge and data about the effects and the effectiveness of policy responses on these issues, and to work out its policy/programming implications to re-establish positive development progress on hunger, jobs and poverty.

This brief outlines key takeaways and recommendations from the workshop presentations and discussions.

Chronic Poverty Report 2023: Pandemic Poverty

The Chronic Poverty Report 2023: Pandemic Poverty sets out to investigate the highly negative effects of the Covid-19 restrictions, and most importantly, the success or otherwise of the measures pursued to mitigate those effects on people in and near poverty.

Read MoreThe Role of Local Resources in Mitigating the Impact of Covid-19

Governments often found it challenging to mitigate the negative socioeconomic impacts of Covid-19 for households in and near poverty. Local efforts were critical to supplement government measures and implement government guidelines.

In Ethiopia, these efforts mobilised a pre-existing, government supported village network system. In Bangladesh, a network of formal and informal strategies played an important role in increasing assistance to people affected by the pandemic, including through industry-based corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives.

This policy brief outlines local responses to and lessons learnt from mitigating the negative socioeconomic impacts of Covid-19.

Delegating Authority in Bangladesh to Manage the Covid-19 Pandemic

Bangladesh, like most countries, grappled with the harsh conditions of Covid-19, with little infrastructure and set up of institutions to deal with the consequences of the pandemic.

A country with a large informal economy, and an even larger export manufacturing sector it is highly dependent on, the Bangladesh government had tough decisions to make when it came to saving and protecting the lives of millions, as well as ensuring continued economic activity to save livelihoods.

To strike a balance between protecting both these important factors, the central government adopted a unique approach of mobilising and enabling the local government to implement a lot of measures. Their approach was area centric, in that the local government recognised the needs of their districts, and that looked different for different areas of the country, whether rural or urban, agricultural or industrial focused.

This policy brief outlines some of the local measures and responses that worked in minimising the impact of Covid-19 on the dense Bangladeshi population.

Mitigating Learning Disruption During Covid-19: Evidence from India

Long school closures in India during the pandemic caused significant learning disruption, with particularly adverse consequences for marginalised girls and boys.

Data from large-scale representative surveys does not show a massive fall in enrolment because of the closures. However, low levels of basic reading and maths skills among school-age children are concerning. In response, various centrally managed interventions took place during the pandemic (e.g. to encourage enrolment, including through social protection).

Schools also undertook measures with a more direct bearing on children’s learning. Continued efforts are needed to reach severely disadvantaged children who are not enrolled.

Migrants’ Vulnerabilities in India During the Pandemic

Migration promotes agglomeration of economic activity in more productive locations and improves employment opportunities for households in less developed regions, alleviating poverty and boosting shared prosperity through remittances.

Most internal migrants’ livelihoods are characterised by circular mobility, mandatory physical presence at work, temporary or seasonal nature of work, and informality. Beside their temporary residential status and lack of access to government welfare schemes, most migrants are vulnerable workers.

The Covid-19 pandemic made them more vulnerable due to its mobility restrictions and total shutdown of the economy during lockdown. The extent of precarity migrants faced depended on existing policies, and how agile policymakers were in responding to the crisis and introducing new policies to protect vulnerable migrants.

Lessons on South Africa’s Social Protection Response to Covid-19

South Africa stands out for its social protection response to Covid-19, especially regarding the expansion of programmes, number of beneficiaries and benefit amount.

At the height of the pandemic, the government introduced the emergency Social Relief of Distress (SRD) grant was introduced for over 10 million unemployed adults and informal workers through a digitised system.

Despite successes in expanding the grant system, digitisation of the system presented challenges and led to exclusion errors. An alternative to the country’s school feeding scheme, the National School Nutrition Programme which regularly fed around 10 million children, could not be found.

Responding to Polycrisis in Ethiopia and Kenya

The spread of Covid-19 was layered on to various intersecting crises (‘polycrisis’), worsening people’s lives and weakening governments’ responses to the pandemic. Many responses to multiple crises focus on single hazards.

This brief highlights effective responses to Covid-19, drought and conflict from Kenya and Ethiopia, which may offer lessons for future policy and programming that equitably address multiple crises.

It focuses on two examples of how governments and local actors have sought to strengthen people’s ability to cope with multiple crises: through collaboration at different levels of governance across sectors; and strengthening resilience through water management.

Measures to Mitigate Pandemic Restrictions

Policy responses to the Covid-19 pandemic in the global South were dominated by movement restrictions and lockdowns imposed in the global North, and not always relevant to the countries or geographical areas where they were imposed.

Countries must be free to decide how to manage a global crisis, so their governments can take decisions that are in the best interests of their citizens, with specific reference to the poorest people, whose lives are already challenging. Many countries’ political and public finance systems could not support mitigating measures to compensate the effects of the lockdowns and restrictions.

Such measures rarely made up for the job losses, income reduction and erosion of social capital caused by closing economies. They also rarely reached some of the groups most affected – including those in the urban informal economy, poor migrants and poor women.

The Pandemic, Informality and Poverty: Rethinking Economic Policy Responses to the Informal Economy

Informal workers, who represent over 60 per cent of all workers globally, were disproportionately impacted by the pandemic restrictions and recession.

The pandemic exposed the pre-existing disadvantages that informal workers face as well as the essential goods and services they provide.

To reduce poverty and inequality going forward, it is important to build on this new-found recognition of the contributions of informal workers and promote an enabling policy and regulatory environment towards them.

“We will die in poverty before dying by COVID”: Young adults and multilayered crises in Afghanistan

Afghanistan experienced an extraordinary situation in 2021 that presents a complex example of how an intensified level of conflict and the global COVID-19 pandemic of added to an increasing prevalence of drought due to climate change has been affecting people’s livelihoods from different angles. In pre-August 2021, the country experienced record-level violence across the provinces. This was followed by the gradual fall of districts, provinces and finally the capital Kabul into the hands of the current de facto authorities, the Taliban.

Meanwhile, like any other part of the world, Afghanistan also experienced the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, which hindered people’s access to jobs, health care and different sources of revenue. Alongside this, the second-worst drought in 4 years (IFRC, 2021) has widely affected the livelihoods of the majority of people who rely on agriculture and livestock as the sole source of income.

There has been limited research into how these situations have combined to affect livelihoods and wellbeing in Afghanistan. This article attempts to advance understanding of this issue and promote research that investigates overlapped crises.

Tanzania Covid-19 Poverty Monitor: Urban and peri-urban areas

Tanzania had its first and most serious wave of Covid-19 from March to June 2020, and adopted the policy responses of partial lockdown, school and international border closures, and banned mass gatherings except religious ones which could be attended with social distancing. In June 2020 some of the strict measures like closing bars, hotels, schools, social events and other businesses were relaxed with some precautions while hygiene and sanitation practices remained in place. The then President of Tanzania, John Pombe Magufuli, instructed to stop publishing data on Covid-19 cases and deaths in late April 2020 for several reasons. First, he was sceptical about the corona testing kits, the process and the integrity of the laboratory technicians. Second, giving data to the citizens was of no help but created fear and panic. He declared that people should pray and rely on God and on traditional medicines while doubting Covid-19 tests. The second and third waves of the pandemic occurred from November 2020 to March 2021 and from June 2021 to October 2021 respectively. The fourth wave occurred from November 2021. President John Pombe Magufuli passed away on 17th March 2021. After his death his successor, President Samia Suluhu Hassan, resumed the publication of Covid-19 cases and deaths and committed Tanzania to a vaccination programme.

She also opened up for external financial assistance to support government’s efforts in overcoming the Covid-19 pandemic in the country. While lockdown was short lived and partial, the fears induced by the pandemic lived on in people’s cautious healthcare practices through to the end of the second wave of Covid-19 (November 2020 to March 2021). The healthcare practices included wearing a face mask, washing hands with soap and running water and avoiding handshakes. And some of the effects of the lockdown, healthcare practices changes resulting from the pandemic, and global economic pandemic related trends have lived on till the present. The third and fourth waves of the pandemic occurred from June 2021 to October 2021 and from November 2021 to the time of the research on which this bulletin is based (March 2022) respectively.

Covid-19 monitoring in rural Tanzania: The pandemic exacerbated pre-existing factors negatively affecting wellbeing

Tanzania avoided a recession due to Covid-19, mainly because it had little stringency in its Covid-19 policy responses. However, the country suffered a decline in real GDP growth rate, and poverty incidence declined marginally between 2020 and 2021. This Bulletin is based on a study which was conducted to disaggregate understanding of who has been affected among the poor and vulnerable, investigate the intersecting disadvantages which may have made it harder for some households and individuals to remain resilient while others were impoverished, and contextualise Covid-19 impacts within a broader examination of the multiple causes of poverty dynamics before and during the pandemic.

The study was conducted in Kongwa and Kilolo Districts, Tanzania, through 48 interviews, which included 27 Life History Interviews (LHIs), 12 Focus Group Discussions (FGDs), and nine Key Informant Interviews (KIIs). It was found that Covid-19 exacerbated pre-existing factors which were negatively impacting interviewees’ incomes but that it did not have adverse economic effects in some areas such as in Rural Kongwa District.

The poor were most affected by an inability to meet costs to practice preventative measures against the pandemic and subsequent treatment if they succumbed to it, and lower earnings due to missed casual labour work. The non-poor were also affected by higher costs incurred on preventive measures against the pandemic and getting treatment if they succumbed to it, and also by a decline in customers for their businesses, and rises in costs of inputs while the prices of products and other goods they traded declined. The main factors for wellbeing improvement before the pandemic were a diversification of crops planted, the acquisition of more land for agriculture, agricultural mechanisation, and doing non-farm businesses besides farm activities. The main factors for wellbeing improvement during the pandemic were avoiding the high costs on Covid-19 infection prevention and treatment, increases in customers after Covid-19 diminished, and getting a loan and using it successfully on income-generating activities. A big policy implication of the findings is that measures to prevent impoverishment are generally very inadequate.

In order to prevent impoverishment and keep poverty declining, even in the face of pandemics like Covid-19, it is recommended that Tanzania needs to target more chronically poor and vulnerable people by strengthening measures against destitution (movement into Wellbeing Level, WB 1); take proper measures for non-pandemic factors which impede poverty reduction, even when there is no pandemic, such as climatic factors, qualities and quantities of agricultural inputs and technologies, agricultural marketing and selling, and taxation on various businesses; and improve social services including education and health.

Authors: Lucia da Corta, Kim Abel Kayunze, Judith Samwel Kahamba, Constantine George Simba, Andrew Shepherd, and Halima Omari Mangi

Poverty and wellbeing before and during Covid-19 in Cambodia: an assessment of trends and correlates

This study investigates factors affecting welfare prior to and during Covid-19. It employs analysis of the Cambodia Living Standards Measurement—Plus Survey 2019/20 data, alongside five rounds of the Covid-19 High Frequency Phone Surveys between May 2020 and March 2021 to assess socioeconomic impacts of the pandemic.

The results point to a range of factors which could contribute to explaining poverty incidence prior to the pandemic. Household resource endowment was an important correlate of welfare, particularly in terms of possession of a mobile phone, ownership of livestock and land and access to electricity. Other factors include access to financial services, education, involvement in non-agriculture businesses, migration and remittances. However, a range of these variables are being constrained during Covid-19. For example, analysis of Covid-19 phone surveys points to the severity of income loss both in terms of breadth (share of households affected) and depth, the latter more pronounced in proportional terms among households in the bottom two quintiles with an already low consumption base, and also severe among IDPoor households. In other words, not only has income loss been deep, but it continues to get deeper over time, starting from a low base. This suggests that there are considerable processes of impoverishment (breadth), but also destitution (depth) in Cambodia as a result of Covid-19.

As a result of shocks, households were forced to rely on a range of coping strategies, especially reducing consumption, taking loans and, for poorer households in later survey waves, accessing social protection. Reliance on support from friends has been reducing over time, perhaps a result of community networks thinning out. Even though the roll-out of cash transfers has eventually reached many ID Poor households, levels may not be adequate resulting in reductions in food consumption among poorer households and continued food insecurity.

The results point to areas for policy and programming focus, including helping to narrow development gaps by area of residence alongside a regional levelling up focused on the Tonle Sap region. Alternatives to borrowing as a coping strategy are also worth considering, alongside improvements in inclusive access and quality of financial services to help mitigate the adverse consequences of indebtedness. Alongside this is a need to focus attention on children who have missed out on school and learning, particularly from poorer households.

Authors: Vidya Diwakar and Vathana Roth, with Tony Kamninga

Welfare of Young Adults amid COVID-19, Conflict, and Disasters: Evidence from Afghanistan

Afghanistan has experienced decades of conflict-related insecurity and disasters, a situation that has been exacerbated by the onset of the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19). This paper employs the Income, Expenditure, and Labour Force Survey (IE&LFS) 2019-20 to quantitatively analyse poverty and welfare loss in Afghanistan. This analysis hence covers the period before August 2021, offering an important baseline to examine deteriorating situations in subsequent years. It finds that rates of poverty and welfare loss increased during the onset of the pandemic, especially among poor households, potentially reflecting new impoverishment as well as destitution processes. Though these rates were comparable across age groups, in absolute terms, they represent approximately 4.7 million young adults living in poverty in 2019-20. Youth-headed households were disadvantaged in terms of a lower asset base. Though they had more years of schooling, and higher rates of salaried employment and migration that both helped protect against poverty, during COVID-19 they were more likely to record a temporary layoff, reflecting the precariousness of youth employment.

Disasters, insecurity, and a range of negative shocks and stressors alongside COVID-19 contributed to welfare loss, and, in some situations, were amplified during the pandemic. Many households reduced expenditures and the quality or quantity of food in response to these shocks, particularly during COVID-19. Food insecurity was a related consequence, heightened during the pandemic, especially among youth-headed households. Other responses common during COVID-19 included an increase in work-related strategies, potentially substituting a decline in social capital within the community. Though the rate of economic activities among women in general was strikingly low, there was a slight increase in employment during COVID-19 among women in poor households, and among women in households experiencing disasters or in insecure areas amid COVID-19. This may point to a potential narrowing of the gender differential in employment in crisis contexts, though this itself is a sign of distress where women in poverty may have no recourse but to engage in precarious work and uphold an increased work burden to meet household needs in times of distress.

Author: Vidya Diwakar

From pandemics to poverty: Hotspots of vulnerability in times of crisis

This brief outlines countries, sub-national areas and populations in or near poverty that need to be explicitly prioritised in the response to coronavirus.

Read More