Thank you for visiting our new Covid-19 Poverty Monitor. To find out more about the project, read our blog.

Areas of concern for the poorest and potential impoverishment

Partial recovery: Most respondents report partial economic recovery since lockdown lifted, but all report continued partial livelihood loss. Some who lost employment due to lockdown in the first bulletin have returned to work. Small business owners report being able to operate again but have seen a reduction in their income. Those producing food for local markets have been able to sell their goods again, though many interviewed report receiving lower prices. Continued challenges in accessing farm inputs is a widely cited challenge in rural areas. Farmers who faced losses earlier in the year report having used savings and taken loans, but there is concern that a lack of access to fertiliser may impact the next harvest, threatening farmers’ recovery in the short term.

Higher costs of staple goods: Many respondents continue to report higher prices for staple goods, particularly food. A VSO survey found food shortage to be the most commonly cited challenge, with many borrowing money and food from friends and relatives or relying on government support.

“[Last time] we talked there was no fertiliser. We got it now, but it wasn’t timely, we didn’t get it when it was necessary, and all our crops were spoiled.”

Increased violence against women and people with disabilities: An increase in gender-based violence (GBV) has been reported by key informants and supported by other sources. A survey by VSO found that 21% of respondents reported an increase in GBV in their communities. The study also found increases in violence to be highest towards people with disabilities, particularly those with multiple disabilities: 5.6% of total respondents reported facing violence compared to 21.7% of people with a single disability and 41.7% with multiple disabilities.

Child marriage: An increase of child marriage was reported by a key informant in Dailekh and this trend has been identified by other sources. A study in four rural districts identified 11 child marriages over the early lockdown period, deemed to be an increase on the normal three-month period.

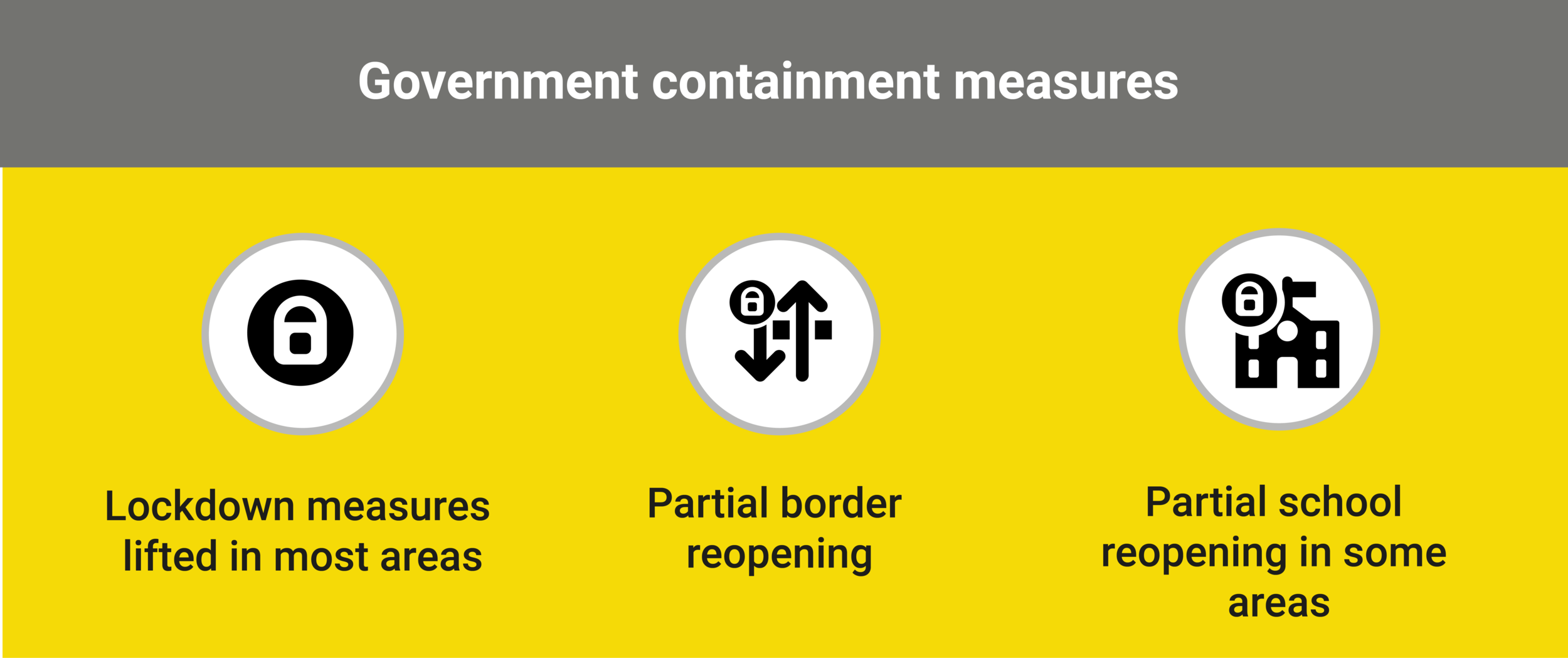

Partial reopening: The government has recently allowed local authorities to decide when to reopen schools. Schools in some regions have resumed partial services, while others remain closed. In Banke, it was reported that some teachers refused to hold classes in areas where schools were to be opened. Children that have not been able to return to school are reported to be facing protection risks, idleness and some are reported to have run away from home.

“Our child got lost and we had to find him and bring him home. He went with his friends. Children running away from home and getting lost has been common here, mostly among 12-16-year-olds. I found this when I went to the police station to report about my child. ”

Groups missing out: Children in areas where schools have not reopened, teachers are not holding classes, or where remote learning has not been provided are still missing out on education. Those without access to a mobile phone or television are unable to access remote learning. A recent World Bank survey also found that only half of schools were providing remote learning support to children with disabilities. A survey of girls enrolled in a girls’ education programme found that 49% were at risk of dropping out due to the pandemic. A VSO survey found that 89% of girls reported increased pressure to do housework or agricultural labour in place of schoolwork.

Coping strategies being employed by poor and non-poor households

Taking loans and drawing on savings: Multiple respondents report taking out loans or drawing on limited savings to pay for daily costs, such as food and rent. Some reported that informal savings groups have not resumed after lockdown restrictions were lifted. The importance of local saving groups as a main support system was highlighted by many respondents.

“I am involved in an organisation where we collect money every month and provide loans, but we have stopped doing so due to lockdown. Even after the lockdown is lifted, things are still not fully on track. It is the same environment of unemployment and fear. ”

Pensions: Older respondents continue to cite pensions and social protection allowances, as their primary livelihood sources and are using this to cope with lost household income from other household members and increasing costs.

Remittances: Nepal has one of the highest rates of remittances in the world, making up 26.9% of GDP in 2019. Several respondents report that they are still receiving remittances from family members working abroad.

Farming: Agricultural households, specifically those with land, report relying on their production to maintain food security. Some respondents without land have identified food security impacts.

““It is hard to manage my necessities and I have reduced my food intake, but we don’t have to sleep empty stomached. We have to buy everything. We don’t have a place of our own, we live in slums.” ”

Increased migration: The continued economic downturn in Nepal is reportedly leading to increased migration in search of work. This includes internal migration and international migration, particularly to India. At the beginning of the pandemic ACAPS reported between 400,000-750,000 people returned to Nepal from India, “and many more are now choosing to return to India in search on income-generating opportunities due to lack of support at home”.

“Due to Covid-19, people who didn’t go to India before are going there now. Many people had business or hotels here, but due to Covid-19, everything was closed so they didn’t have any work and money to pay their rent. They are going to India as they don’t have any other choice. There is no proper daily wage work here, otherwise, they would have worked here.”

Programmes in place to mitigate impoverishment due to Covid-19

Relief for farmers: At the beginning of the pandemic the Government of Nepal announced an emergency relief package for farmers, with cash and farm input support based on land entitlement and size. Several respondents expressed concern with the lack of transparency and poor targeting of support, as well as delays in receiving support that led to crop losses; this finding is supported by other studies.

Youth Employment Transformation Initiative: This four-year programme aims to promote domestic employment and enable poor and vulnerable youth to gain access to employment, skills development and capacity building. Funded by the World Bank, it was agreed in late 2019, but will now be front-loaded as part of the Bank’s Covid-19 response.

Key external sources

To find out more about the impacts of Covid-19 on poverty in Nepal, please explore the following sources that were reviewed for this bulletin:

CPAN country bulletins are compiled using a combination of original qualitative data collected from a small number of affected people in each country, interviews with local leaders and community development actors, and secondary data from a range of available published sources. Interviews for this bulletin were conducted in Banke, Nukawot and Kathmandu between November 23rd and December 1st 2020. See our Covid-19 Poverty Monitor methodology note for more details on how we collected this data.

This project was made possible with support from HelpAge International.

World Bank