By Duncan Green, strategic adviser for Oxfam GB

Local governance performance index

Went to an enjoyable panel at ODI last week, with the wonderful subtitle ‘Shouting at the system won’t make it work!’. It presented new research on how to improve the accountability of local government in Tanzania. Here’s the paper presented by two of the authors, Anna Mdee and Patricia Tshomba, the first of a series.

The research is about how you construct a local government performance index that means something to local people. It’s research rather than consultancy, so the task is not to produce an index for others to implement, but to work out how to do it.

And it turns out (surprise surprise) to be really difficult. According to one of the authors, Anna Mdee ‘We found a big gap between theory and practice. Practice is much more multiple, with parallel negotiations, the remains of a one party system, the formal state, extremely influential faith organizations, civil society organizations. So it’s hard to establish who is being held to account. We found lines of accountability, but also ‘lines of blame’ – everyone blames everyone else, not always along the same lines. Government tries to push blame all the way down to the villages (which have massive responsibilities and no resources).’

The researchers opted for building an index as a starting point for triggering conversations about problems and how to fix them. Through a combination of workshops, focus groups and interviews, they identified those problems as:

- Politicians are not concerned with peoples’ problems

- Councillors and other local representatives feel they are misjudged

- Lack of communication, openness, cooperation and togetherness

- No platform to bring together stakeholders

- Lack of important documents and knowledge

- Weak culture of reading

- Shortage of funds (‘District officials reported that the social welfare department has many activities and manpower but has only a budget of 1 million Tanzanian Shillings (approx. £360) per month’).

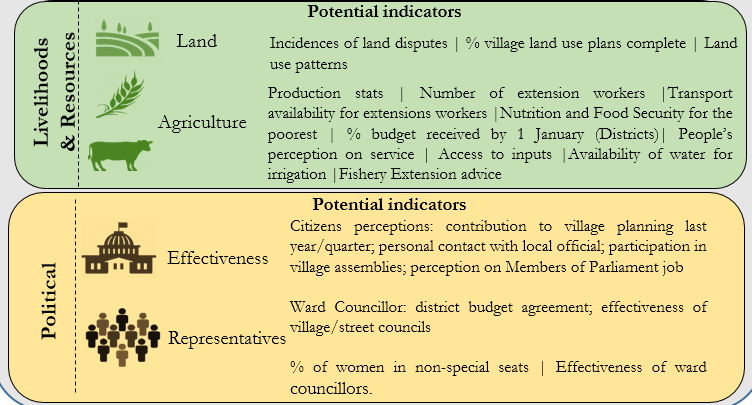

Example of indicators

They used the conversations to identify a draft set of indicators, went back to consult and refine them, and came up with the ones in the diagram, with the litmus test being ‘if you had this, would it make any difference? Would anyone use it?’

The purpose of this is definitely not advocacy of the finger-wagging variety, but rather ‘getting beyond the blame game’: ‘We see potential in using a Local Governance Performance Index as a collaborative problem-solving tool, that helps to move from a list of complaints about problems that local officials and representatives have limited capacity to resolve, to a collective understanding between citizens and local government about where blockages lie, and what they can do together to overcome them.’

Which is really interesting and echoes in part our own governance work in the Chukua Hatua programme: we started off helping local communities ‘demand accountability’ from local officials, but moved to something more collaborative when those officials said they would love to be more accountable, but had little idea what their roles and responsibilities actually were.

I’m a sceptic on finger wagging (see one of my favourite cartoons on ‘speaking truth to power) and love the focus on collective problem solving, on getting local people to identify the right indicators and the acknowledgement of the complexity of local governance. But I did worry that by aiming purely for using the index to trigger conversations, they were missing a trick.

In particular, they reject the idea of a single composite index, because they think that would prompt a slide into attempts to ‘game’ the index, and this would lose the emphasis on collective problem solving. And anyway, if you really listen to your interviewees, you are likely to come up with a different index for each village, which messes up any kind of comparison anyway.

But we know from experiences like PAPI in Vietnam, and others in Uganda (as well as in lots of other settings from the UN to corporates) that a league table focuses the minds of leaders like nothing else – they really don’t want to be beaten by their neighbours and rivals. Anna replied to my question on this by saying ‘I’m an anthropologist, so instinctively cautious about quantification, and the distortion produced through overemphasis on proxy indicators’. Actually, there’s lots of quantification in the index, what she’s opposing is over-simplification, which is laudable, but could carry a cost in lost influence.

Has anyone done a comparative study of different approaches to local government indexes – how they are designed, who uses them, what impact they have etc? If so, I’d love to read it.

This blog was originally posted on From Poverty to Power - Oxfam Blogs

To know more about CPAN's work on Local Governance, visit the project page Holding local government to account: Can a performance index provide meaningful accountability?